Street Fighter II Champion Edition: The $2.3 Billion Arcade Phenomenon That Conquered the World

Street Fighter II' Champion Edition (1992) made $2.3 billion in arcades. First fighting game with playable bosses and mirror matches. Ran on Capcom CPS-1 hardware.

Street Fighter II': Champion Edition, or as it was known in Japan, Street Fighter II Dash (with that iconic prime symbol), wasn't just an update. It was a seismic shift that would go on to generate $2.3 billion in worldwide arcade revenue, making it one of the three highest-grossing arcade games ever created. Only Pac-Man and Space Invaders sit above it on that legendary throne.

The Sequel That Wasn't Supposed to Exist

When the original Street Fighter II: The World Warrior exploded onto arcades in 1991, nobody at Capcom fully anticipated what they had unleashed. The game was selling so fast that operators couldn't get enough cabinets. Lines stretched out arcade doors. Kids spent their lunch money daily just to get a few rounds in. By early 1992, Capcom faced a choice: start developing a full sequel (which would take years) or give the hungry masses something to tide them over.

They chose door number two, but what they delivered was far more than a simple patch. Champion Edition, released in March 1992 in Japan, addressed the single biggest complaint players had: "Why can't I play as the bosses?" It seems obvious now, but back then, boss characters were meant to be unplayable walls of difficulty. Capcom decided to tear down that wall.

Now You Can Be the Boss

The Four Grand Masters, previously exclusive to the CPU, stepped into the spotlight as fully playable fighters. Balrog, the devastating boxer (called M. Bison in Japan due to trademark concerns with a certain heavyweight champion), brought pure American aggression. Vega, the Spanish claw fighter known as Balrog in Japan, introduced wall-diving acrobatics and narcissistic flair. Sagat, the towering Muay Thai king, could finally be controlled by human hands, his Tiger Shot and Tiger Uppercut now answering to player inputs rather than AI patterns.

And then there was M. Bison himself, the Shadaloo dictator wielding Psycho Power (Vega in Japan, completing the name shuffle). Playing as Bison felt transgressive, like the game was letting you behind the curtain. His Psycho Crusher, Head Press, and Scissor Kick became tools in your arsenal rather than threats to survive.

But Capcom knew these characters couldn't simply be copy-pasted from their CPU incarnations. The bosses were intentionally overpowered as AI opponents. For competitive play, they needed balancing, and balance they received. Damage values were adjusted, recovery frames were tweaked, and suddenly these four titans became part of the competitive ecosystem rather than dominators of it.

Mirror Matches Change Everything

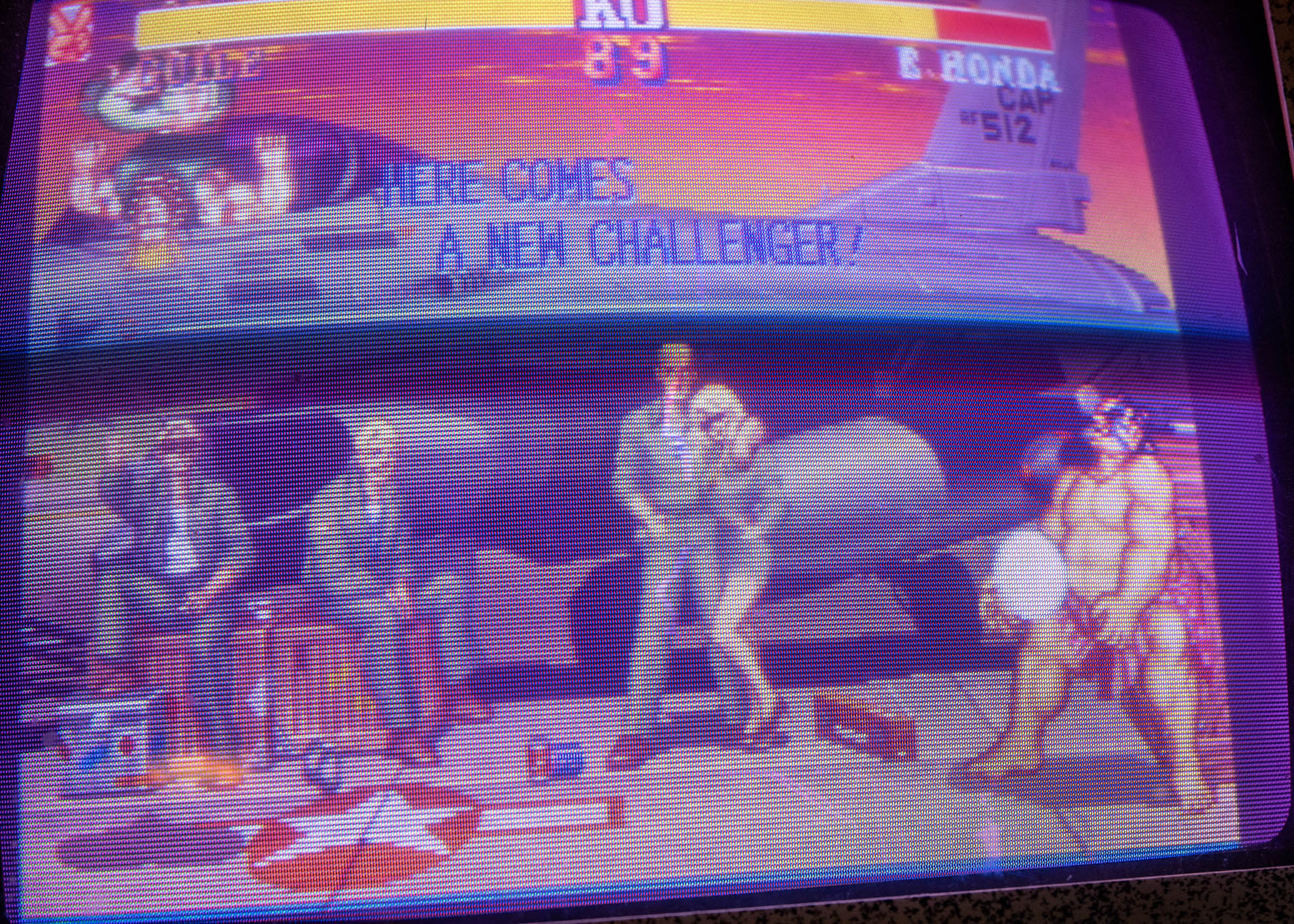

Champion Edition introduced another revolutionary concept: mirror matches. For the first time in Street Fighter history, two players could select the same character. Ryu versus Ryu. Ken versus Ken. Chun-Li versus Chun-Li. To distinguish players, alternate color palettes were introduced, giving fighters secondary costumes that became iconic in their own right. Who doesn't remember pink Ryu?

This feature seems basic now, but in 1992 it fundamentally changed competitive dynamics. No more arguments about who "got" to play as Ryu. No more character selection becoming a mini-conflict. Both players could prove who was the better Ryu, the better Ken, the better anything. It was pure skill testing, stripped of character-based excuses.

The Dream Team Behind the Machine

The original Street Fighter II took about two years to develop with a team of 35 to 40 people, an enormous undertaking for the era. The key figures behind this revolution included Yoshiki Okamoto, the legendary producer who would later help create Biohazard (Resident Evil) and even the mobile phenomenon Monster Strike. Okamoto had transferred from Konami to Capcom, where he spent nearly two decades shaping gaming history.

Noritaka Funamizu served as producer, a man whose Capcom career began in an unusual way: he befriended Okamoto while playing catchball at Capcom before transitioning to game development. By 1997, he would become director of Capcom's First Development Division, overseeing not just Street Fighter but the Darkstalkers series and countless other 2D fighting classics.

Akira Nishitani handled game design, a man who openly admitted he "disliked belt-scrolling action games," which motivated him to strengthen Street Fighter's one-on-one combat mechanics. Working alongside him was Akira Yasuda, known in the industry as Akiman, who handled character design and planning. Both came from Final Fight's development team, bringing that experience into the fighting game arena.

The character programmers had a surprisingly casual method for assigning who worked on which fighter: rock-paper-scissors. ERICHAN coded E. Honda, IKUSAN.Z handled Zangief and M. Bison, and SHOEI programmed the iconic Ryu and Ken. These weren't just coders; they were the architects of movesets that would be studied and debated for decades.

Balance Changes That Mattered

Beyond adding the bosses, Champion Edition refined the existing eight World Warriors. Ryu and Ken, who had been nearly identical in the original, began their divergence here. Ken's Shoryuken gained the ability to hit multiple times while on fire, a change that would become his signature across all future versions. Ryu remained the pure fundamentalist, his moves prioritizing consistency over flash.

Chun-Li received something special: her flip attacks were restored from the location test versions of World Warrior, where they had been removed before wide release. These additional moves gave her more offensive options, helping her compete with the newly expanded roster. The competitive meta shifted, evolved, and players had to adapt to a game that felt both familiar and fresh.

CPS-1: The Hardware That Powered a Revolution

Champion Edition ran on Capcom's CPS-1 (Capcom Play System) hardware, the same board that powered the original. This arcade board used a Motorola 68000 processor running at 10-12 MHz as its main CPU, with a Zilog Z80 at 4 MHz handling sound. The audio came through a Yamaha YM2151 chip paired with an Oki MSM6295, producing the iconic music and sound effects that still echo in the minds of arcade veterans.

Here's the fascinating part: Capcom's own developers considered CPS-1 "honestly the minimum level" of hardware at the time. According to interviews with Okamoto and Nishitani, they described it as "outdated by several years" compared to competitors, lacking rotation and scaling capabilities. Yet Street Fighter II's success made the board seem revolutionary to the outside world. The custom chips alone cost approximately $9.8 million to develop, but the investment paid off exponentially.

The CPS-1 used 16x16 dot tiles (sprites) arranged in layers to create characters. Champion Edition was the 14th game to use this hardware, and its success would ensure many more followed. However, this same architecture would prove vulnerable to something Capcom never anticipated: bootleggers.

Numbers That Defy Belief

The commercial success of Champion Edition borders on the unbelievable. In Japan alone, 140,000 arcade units sold at ¥160,000 (approximately $1,300 USD) each. That's ¥22.4 billion, or roughly $182 million in hardware revenue just from Japanese sales. Adjusted for 2024 inflation, that equals about $420 million from one country.

In the United States, between 20,000 and 25,000 units found homes in arcades from coast to coast. Combined with Japan, Champion Edition moved over 160,000 units across these two markets alone. Game Machine magazine listed it as the most successful table arcade cabinet of May 1992, and it would go on to become the second highest-grossing arcade game of the entire year in Japan (only the original World Warrior beat it).

The worldwide revenue figure? $2.3 billion. That's not a typo. Champion Edition generated two point three billion dollars in coin-drop revenue across global arcades. Adjusted for today's money, that equals approximately $5.15 billion. This places it among the top three highest-grossing arcade games in history, trailing only Pac-Man and Space Invaders.

When you combine all Street Fighter II versions together (World Warrior, Champion Edition, Turbo, Super, and beyond), the total revenue reaches an estimated $10.61 billion. In 1993 alone, the franchise generated $1.5 billion annually, making it the highest-grossing entertainment product of that year, outearning even Jurassic Park.

The Rainbow Edition Conspiracy

Champion Edition's popularity created an unexpected problem: demand vastly exceeded supply. Arcade operators waited months for boards while their competitors printed money with cabinets already installed. Into this vacuum stepped Taiwan-based bootleggers, most notably a mysterious outfit called "Hung Hsi Enterprise." What they created would accidentally change Street Fighter history.

Street Fighter II' Rainbow Edition wasn't just a copy; it was a fever dream modification. Characters could throw Hadokens mid-air. Fighters could transform into other characters mid-match. Gameplay speed increased dramatically. The title logo used Guile's color palette, creating a rainbow effect that gave the bootleg its name. It was chaos, it was broken, and players loved it.

Bootleggers marketed Rainbow as an official sequel, selling it cheaper than legitimate Champion Edition boards. Dozens of bootleg variants of Champion Edition circulated through arcades worldwide. In certain countries, the Rainbow Edition actually became more popular than Capcom's official release.

In January 1993, Capcom took out warning advertisements in Game Machine magazine alerting operators about the piracy problem. They threatened to cut off game supplies to any arcade running bootleg boards. But something interesting happened behind closed doors: Capcom's own staff started playing Rainbow Edition.

Developers obtained bootleg boards and analyzed the code, partly out of curiosity, partly to understand what players found appealing. What they discovered was remarkable: the bootleggers had found a way to accelerate game speed using code that Capcom's own engineers hadn't developed. The speed increase worked, and players clearly enjoyed it.

Producer Noritaka Funamizu later confirmed that during Super Street Fighter II's development, Yoshiki Okamoto gave him a direct order: "Make Rainbow's gameplay official." The result was Street Fighter II' Turbo: Hyper Fighting, released on December 17, 1992, which incorporated faster gameplay and even aerial special moves inspired by the bootleg. A pirated game had influenced its own official sequel.

World Domination

Champion Edition didn't just succeed; it conquered. In Japan, Game Machine ranked it the number one table arcade cabinet for May 1992. In the United States, RePlay magazine placed it at the top of upright cabinet earnings charts from May 1992 through September, outperforming even the newly released Mortal Kombat. The Amusement and Music Operators Association (AMOA) crowned it the highest-grossing dedicated arcade game of 1992 in America.

By 1993, it remained in Japan's top four highest-grossing arcade games. The conversion kit version (allowing operators to upgrade existing cabinets rather than buy new ones) landed in the top five conversion kits of 1993. Everywhere you looked, Champion Edition dominated.

The 1992 Gamest Cup Street Fighter II Dash Championship attracted 4,000 participants, won by a player named Tachikawa. This wasn't just a game tournament; it was one of the earliest precursors to modern esports. Players from across Japan gathered to prove their skills in organized competition, a format that would eventually evolve into today's EVO Championship Series.

Guinness Records and Legacy

The Street Fighter II series, with Champion Edition at its commercial peak, earned multiple Guinness World Records in the 2008 Gamer's Edition. It was recognized as the "First Fighting Game to Use Combos," though the combo system was actually discovered accidentally by players who found they could chain attacks during hit-stun frames. What started as a glitch became a fundamental fighting game mechanic.

It also earned the record for "Most Cloned Fighting Game," evidenced by the dozens of bootleg variants and countless imitators that flooded arcades trying to capture Street Fighter's magic. And it held "Biggest-Selling Coin-Operated Fighting Game," a record that stood for years thanks to those astronomical sales figures.

By 1994, an estimated 25 million Americans had played Street Fighter II in some form. The series revitalized the arcade industry during the early 1990s, bringing foot traffic back to game centers that had been struggling since the 1983 crash. Across all versions, more than 60,000 cabinets sold worldwide, and home versions moved 15.5 million units across various platforms before Super Smash Bros. Ultimate eventually surpassed that record.

The Characters That Became Icons

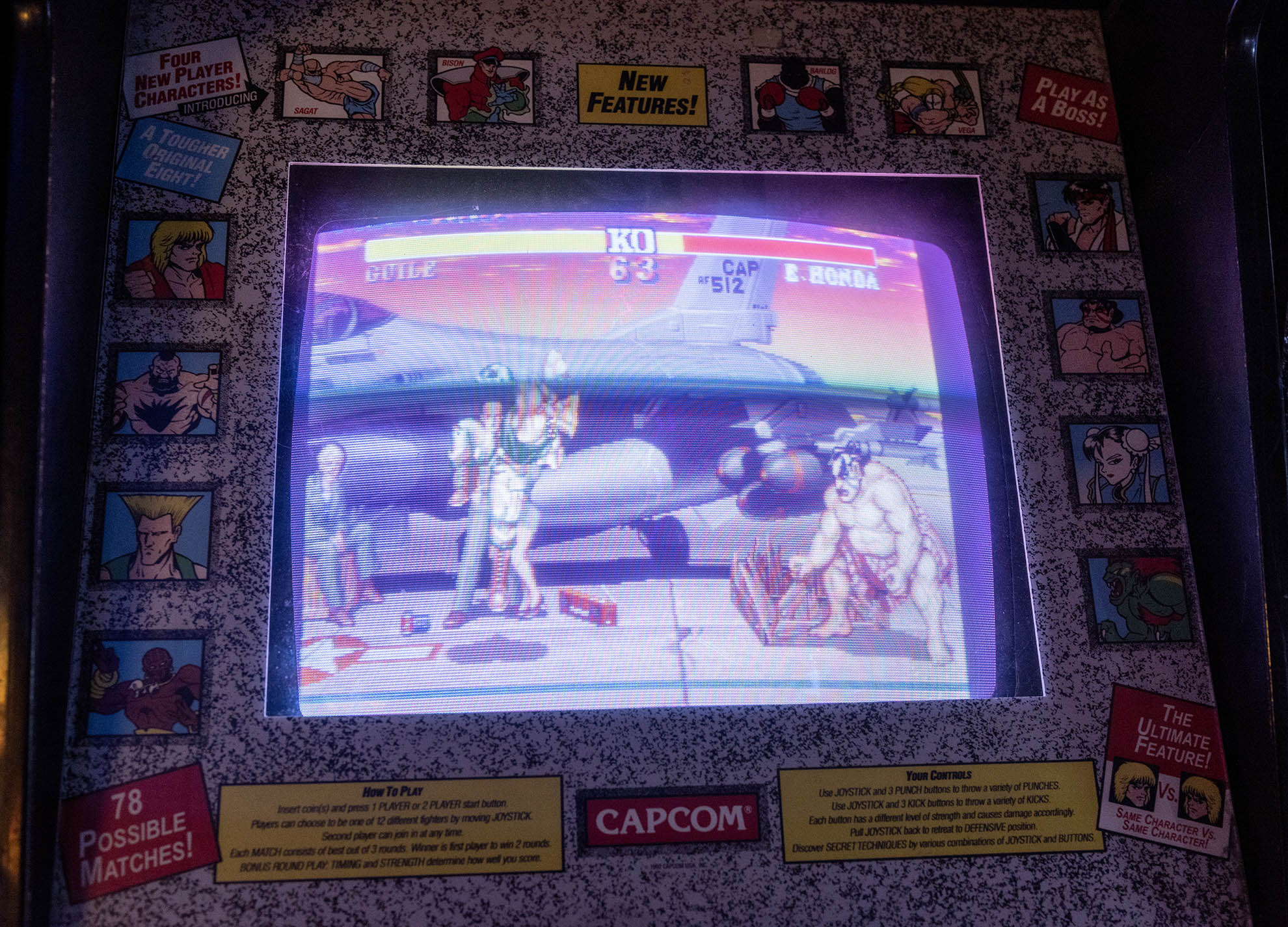

Champion Edition's 12-fighter roster set the template for fighting game character diversity. The original eight World Warriors each represented different nations and martial arts: Ryu and Ken with Shotokan karate from Japan and the USA, Chun-Li bringing Chinese kung fu (and becoming the first playable female fighting game character), Guile representing the US Air Force with his Sonic Boom projectile, Blanka channeling Brazil with electric attacks, Zangief embodying Soviet wrestling power, Dhalsim stretching yoga to supernatural lengths from India, and E. Honda slapping his way to victory with Japanese sumo.

Adding the four bosses rounded out a roster that covered virtually every major fighting style players might want to explore. Balrog's boxing, Vega's Spanish ninjutsu and fencing, Sagat's Muay Thai, and M. Bison's mysterious Psycho Power completed a cast that influenced every fighting game to follow.

Home Ports Spread the Gospel

Champion Edition eventually reached home consoles, bringing the arcade experience to living rooms worldwide. The Sega Genesis and Mega Drive received "Street Fighter II': Special Champion Edition" in 1993, a solid port that let console owners finally play as the bosses. The PC Engine and TurboGrafx-16 got a more straightforward "Street Fighter II': Champion Edition" port the same year. Brazil even received a Master System version through Tec Toy in 1997, proving the game's appeal stretched across console generations.

Why Champion Edition Still Matters

More than three decades later, Champion Edition's influence permeates every fighting game released. The concept of updated versions with balance patches? Champion Edition pioneered it. Character-based alternate costumes? Thank those alternate color palettes. Previously unplayable boss characters becoming roster additions? Champion Edition broke that barrier first.

The competitive fighting game community, from local weeklies to the EVO Championship Series, traces its lineage directly back to the arcades where Champion Edition cabinets once drew crowds. For more fighting game history, see BlazBlue's 17th anniversary. John Romero has stated that Doom's deathmatch mode was influenced by the face-to-face competitive atmosphere Street Fighter II created. That ripple effect extends through decades of multiplayer gaming.

At the 1992 Gamest Grand Prize (the 6th annual awards), Champion Edition earned the number one spot for Best Income and Annual Hit Game, cementing its place in arcade history. It also placed third for Best VGM (Video Game Music), behind only Konami's Xexex and Taito's Metal Black. Not bad for what was technically an "update."

When developers today talk about the "golden age of arcades," they're talking about the era Champion Edition dominated. When fighting game veterans reminisce about quarter-up challenges and arcade rivalries, they're remembering cabinets just like this one. When modern esports commentators trace the origins of competitive gaming, the path leads back to 1992 and the game that let you finally be the boss.

Street Fighter II Champion Edition wasn't just a game. It was a cultural moment, a commercial juggernaut, and the blueprint for competitive gaming's future. Thirty years later, that legacy hasn't faded. It's been built upon by every fighting game that followed, standing as proof that sometimes the best sequel is the one that simply gives players what they've been asking for.

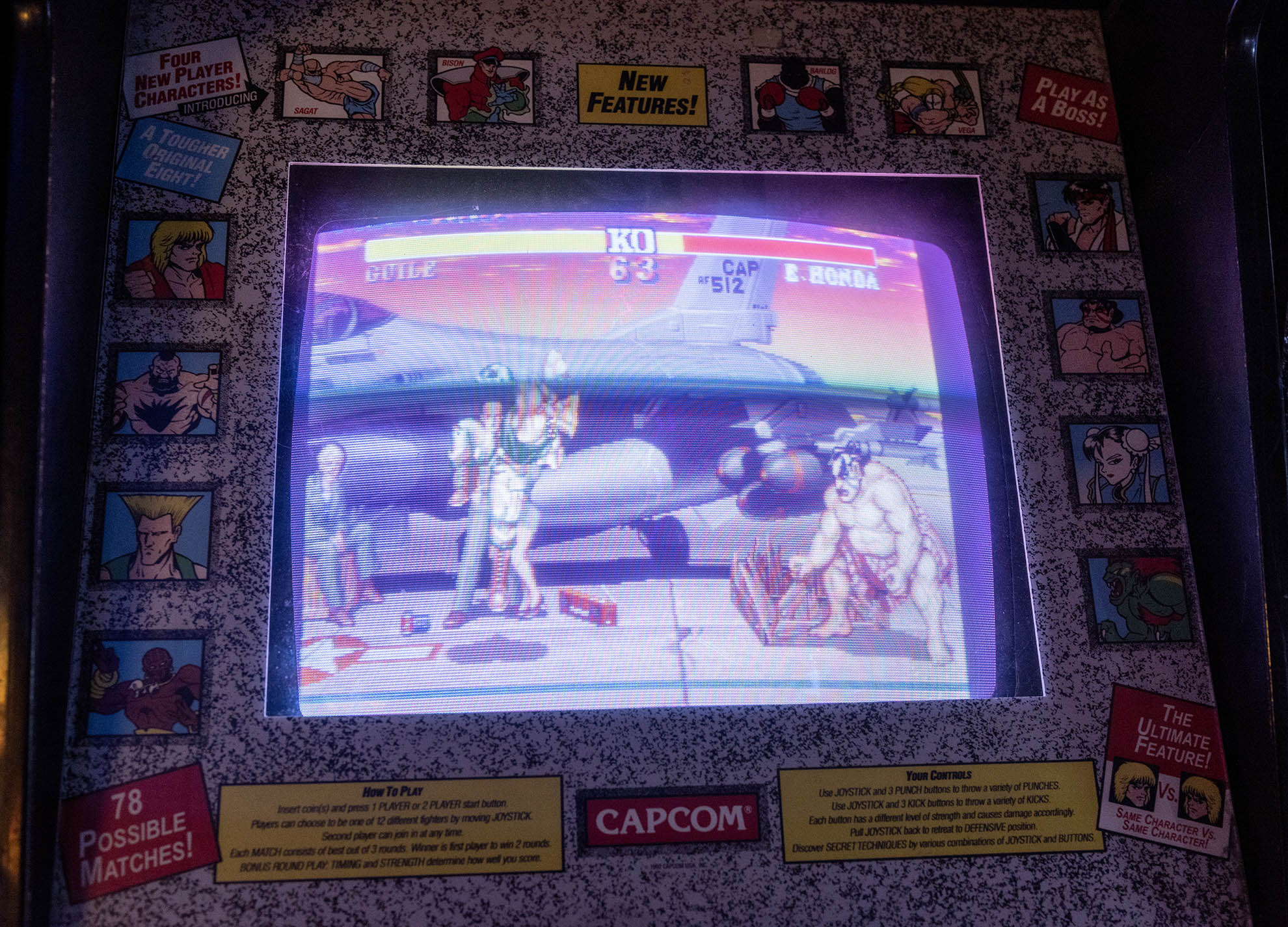

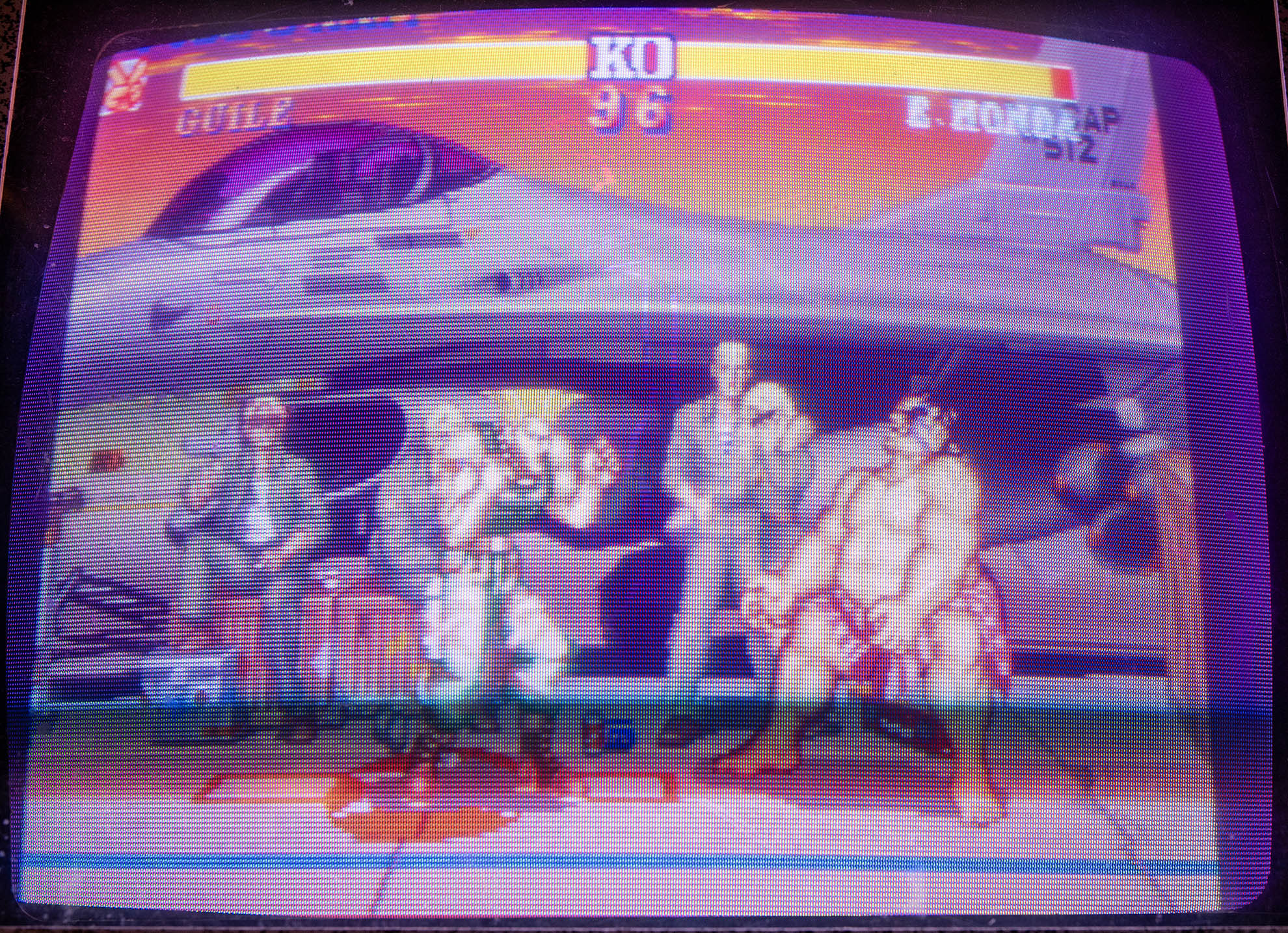

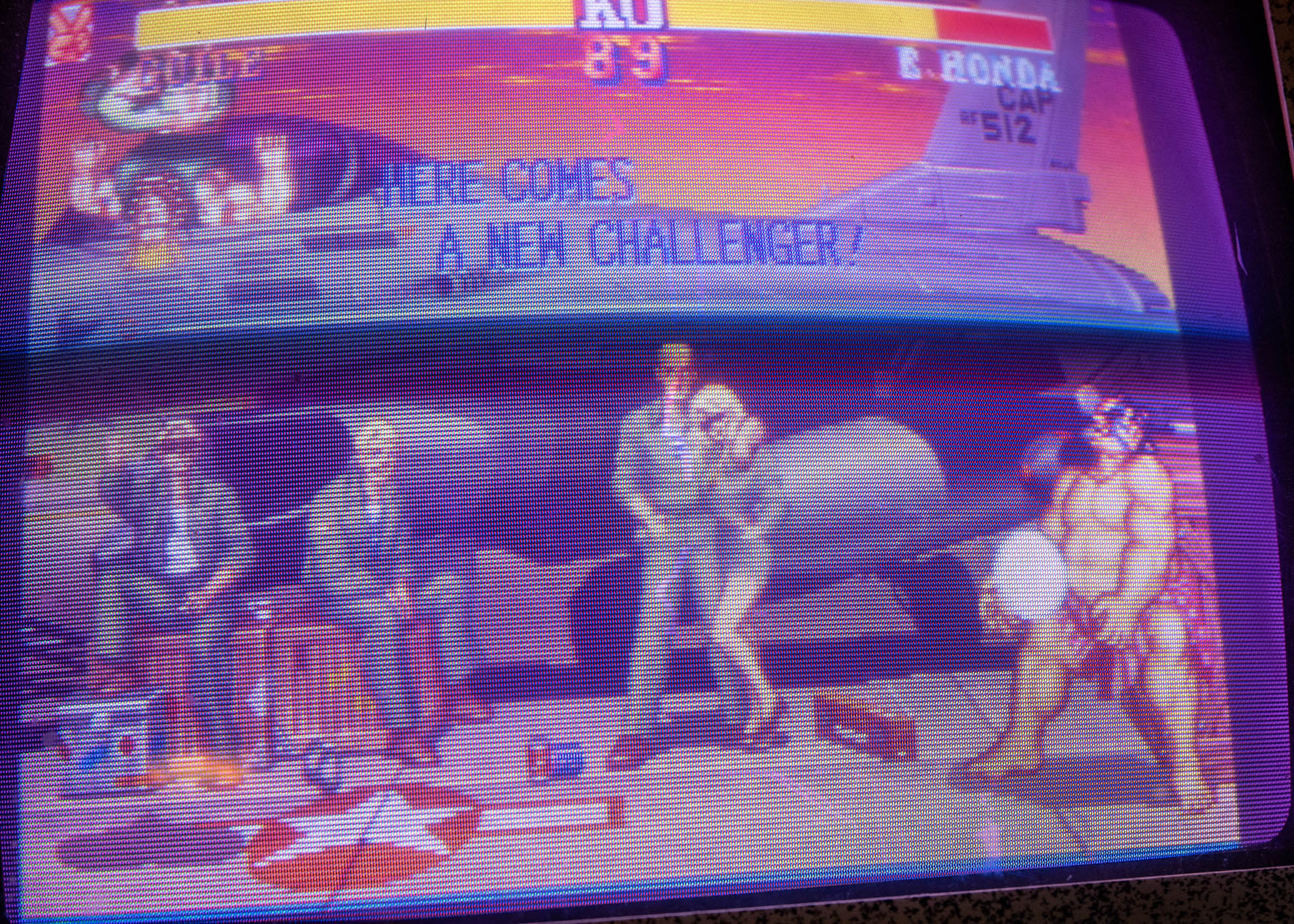

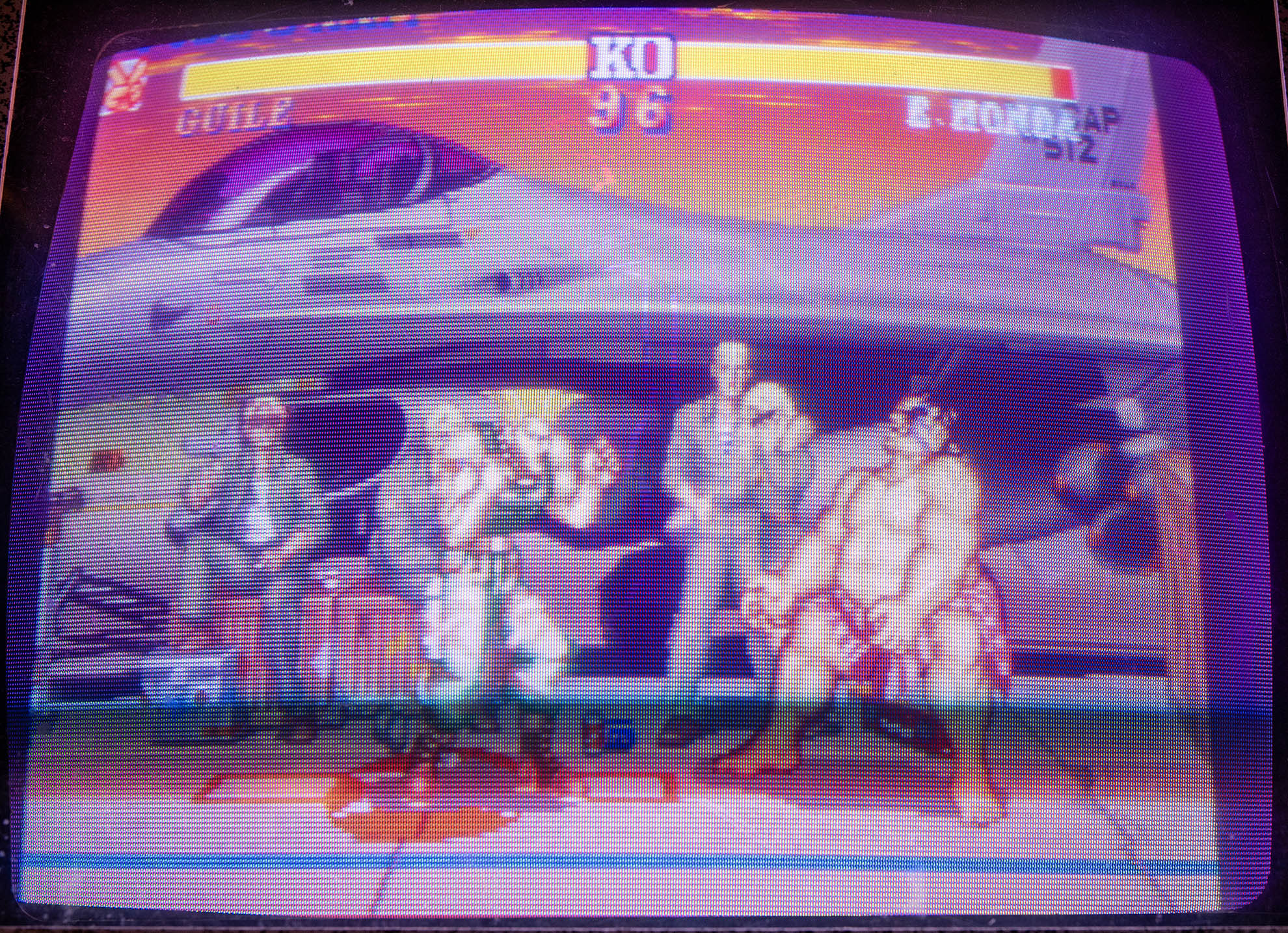

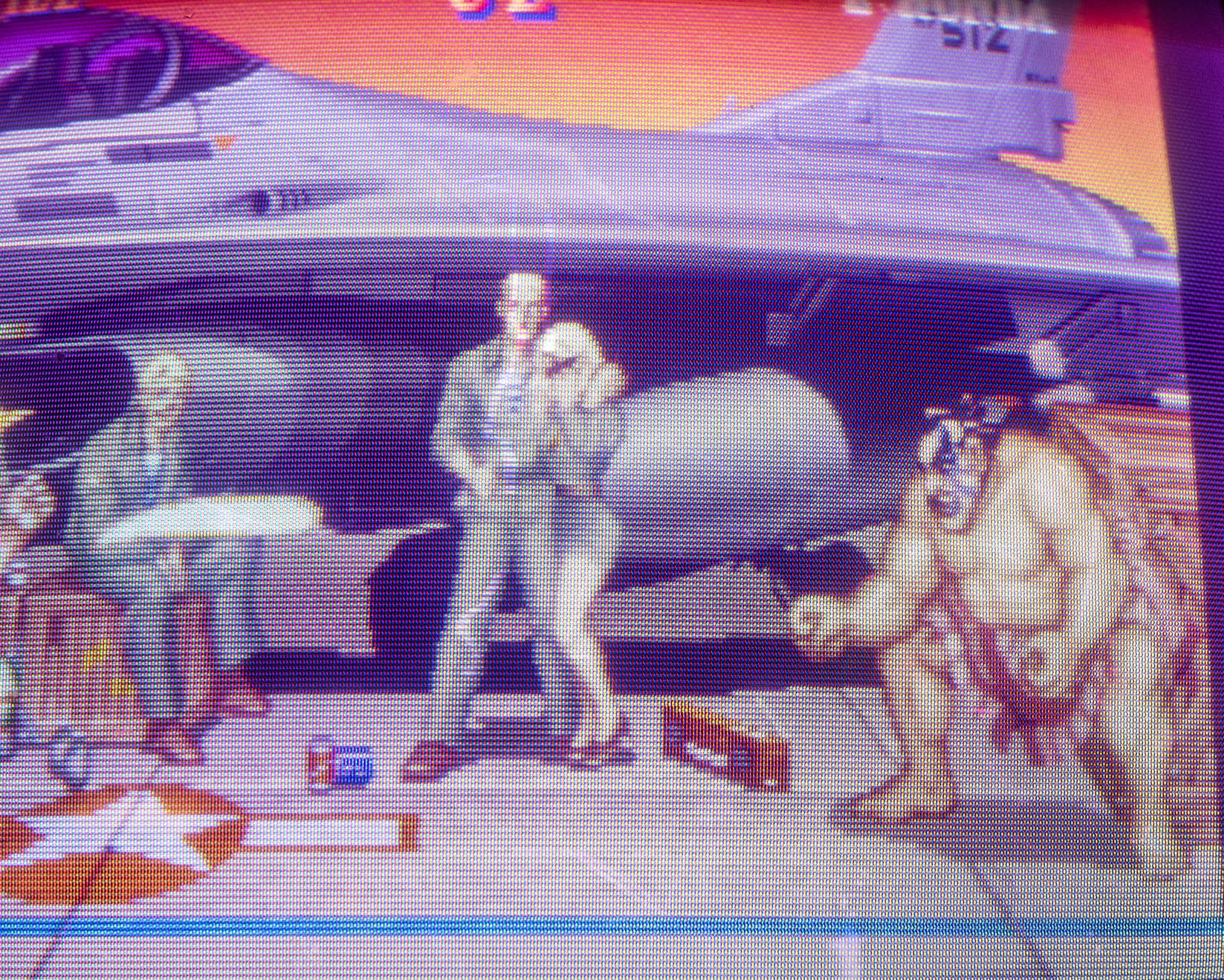

All arcade cabinet photos taken by the author at The Pixel Bunker.

For more arcade classics, see X-Men and Snow Bros.\n\nThere's a moment every arcade kid from 1992 remembers. You walk into your local game center, the familiar electronic symphony washing over you, and there it is: a crowd three deep around a Street Fighter II cabinet. But something's different. Someone is playing as M. Bison. Not fighting him. Playing as him. Your jaw drops. The future of fighting games has arrived, and it wears a cape and shoots Psycho Power.

Game Information

| Title | Street Fighter II': Champion Edition |

| JP Title | ストリートファイターII' |

| Developer | Capcom |

| Producer | Yoshiki Okamoto |

| Release | March 1992 (Japan) |

| Platform | Arcade (CPS-1) |

| Genre | Fighting |

| Players | 1-2 |

| Units Sold | 140,000+ (Japan) |

| Revenue | $2.3 Billion (worldwide) |

Gallery

Get Gaming News and Features First

Stay updated with the latest gaming news and exclusive content.