Donkey Kong: The 1981 Arcade Game That Saved Nintendo and Created Mario

Donkey Kong (1981) saved Nintendo with $280M revenue. Shigeru Miyamoto's first game introduced Mario (then Jumpman) and invented the platformer genre.

The year is 1981. In a warehouse in Tukwila, Washington, two thousand arcade cabinets sit collecting dust. Each one represents money that Nintendo of America doesn't have. The machines are Radar Scope units, a space shooter that had done reasonably well in Japan but completely flopped in America. Nintendo of America's president, Minoru Arakawa, had bet the company's modest budget on ordering 3,000 of these cabinets. Only a thousand had sold.

Arakawa was in trouble. His father-in-law happened to be Hiroshi Yamauchi, the president of Nintendo back in Japan. This was both a blessing and a curse. Yes, it meant he had connections. But it also meant failure wasn't really an option. Arakawa made the call. He needed a new game, something that could be retrofitted into those dead Radar Scope cabinets before the company went under.

Yamauchi's response would change video game history forever. He assigned the project to a young staff artist who had never designed a video game in his life. His name was Shigeru Miyamoto.

The Popeye That Never Was

Miyamoto wasn't exactly an obvious choice. He had joined Nintendo in 1977 as an industrial designer, working on the physical appearance of arcade cabinets rather than what went inside them. But Yamauchi saw something in him. Perhaps it was his art school background, or maybe his fresh perspective unburdened by industry conventions. Whatever the reason, Miyamoto found himself with a budget of $267,000 (roughly $923,000 in today's money) and a deadline that could make or break Nintendo's American ambitions.

His first idea was to make a game based on Popeye. The spinach-loving sailor was hugely popular, and Miyamoto envisioned a love triangle between Popeye, Bluto, and Olive Oyl. There was just one problem. King Features, which owned the Popeye license, said no.

Most developers would have panicked. Miyamoto simply shrugged and created his own characters instead.

Bluto, the brutish villain, became a giant ape. Miyamoto drew inspiration from King Kong and the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast. He wanted something that looked threatening but wasn't genuinely evil. "Nothing too evil or repulsive," he later explained. This ape would be the protagonist's pet who had gone rogue.

Olive Oyl transformed into a damsel in distress with a pink dress and brown hair. She would eventually be named Pauline, after Polly James, the girlfriend of Nintendo of America's warehouse manager Don James. Some believe the name also referenced "The Perils of Pauline," an early 20th century film serial about a woman in constant danger.

And Popeye? He became a squat carpenter in red overalls with a big nose and a mustache. Those distinctive features weren't artistic choices. They were technical necessities. With the limited pixels available, Miyamoto couldn't draw a mouth, so he added a mustache. He couldn't animate hair, so he gave the character a cap. The overalls helped distinguish the arms from the body during movement.

This unnamed carpenter would soon become the most famous character in video game history.

The Stupid Ape

Naming the game proved almost as challenging as designing it. Miyamoto wanted something that communicated the personality of his villain. He grabbed a Japanese-to-English dictionary and started looking for words.

He found "donkey," which the dictionary described as meaning stubborn or foolish. Perfect for his antagonist. Then he added "Kong," which in Japan had become slang for a large gorilla thanks to the popularity of King Kong movies. In Miyamoto's mind, the title meant "Stupid Ape."

When Nintendo of America's sales team heard the name, they hated it. They thought Americans would be confused or, worse, think it was a joke. Some suggested changing it to something more marketable. Miyamoto and Yamauchi refused. Donkey Kong it would be.

They were right to stand firm. That unusual name would become one of the most recognizable in gaming.

Learning to Jump

Miyamoto wasn't working alone. Gunpei Yokoi, Nintendo's legendary engineer who had created the Game & Watch handhelds, served as the project's supervisor. The actual programming fell to a team from Ikegami Tsushinki, an outside contractor. Four programmers, Komonome Hirohisa, Iinuma Minoru, Nishida Mitsuhiro, and Murata Yasuhiro, spent three months turning Miyamoto's vision into code.

Here's a wild detail that often gets overlooked. None of these people had ever made a video game before. Not Miyamoto. Not the Ikegami team. They were figuring it out as they went, bringing a kind of creative freedom that more experienced developers might not have allowed themselves.

Miyamoto's original design had the player avoiding obstacles by climbing ladders. Barrels would roll down from the top of the screen, and you'd scurry up ladders to dodge them. It was fine, but Yokoi thought it was missing something.

"What if he could jump?" Yokoi suggested.

That single question changed everything. In 1981, jumping in video games was rare. Yokoi's suggestion gave Donkey Kong its signature mechanic and, according to Guinness World Records, made it the first true platform game ever created.

Four Floors of Chaos

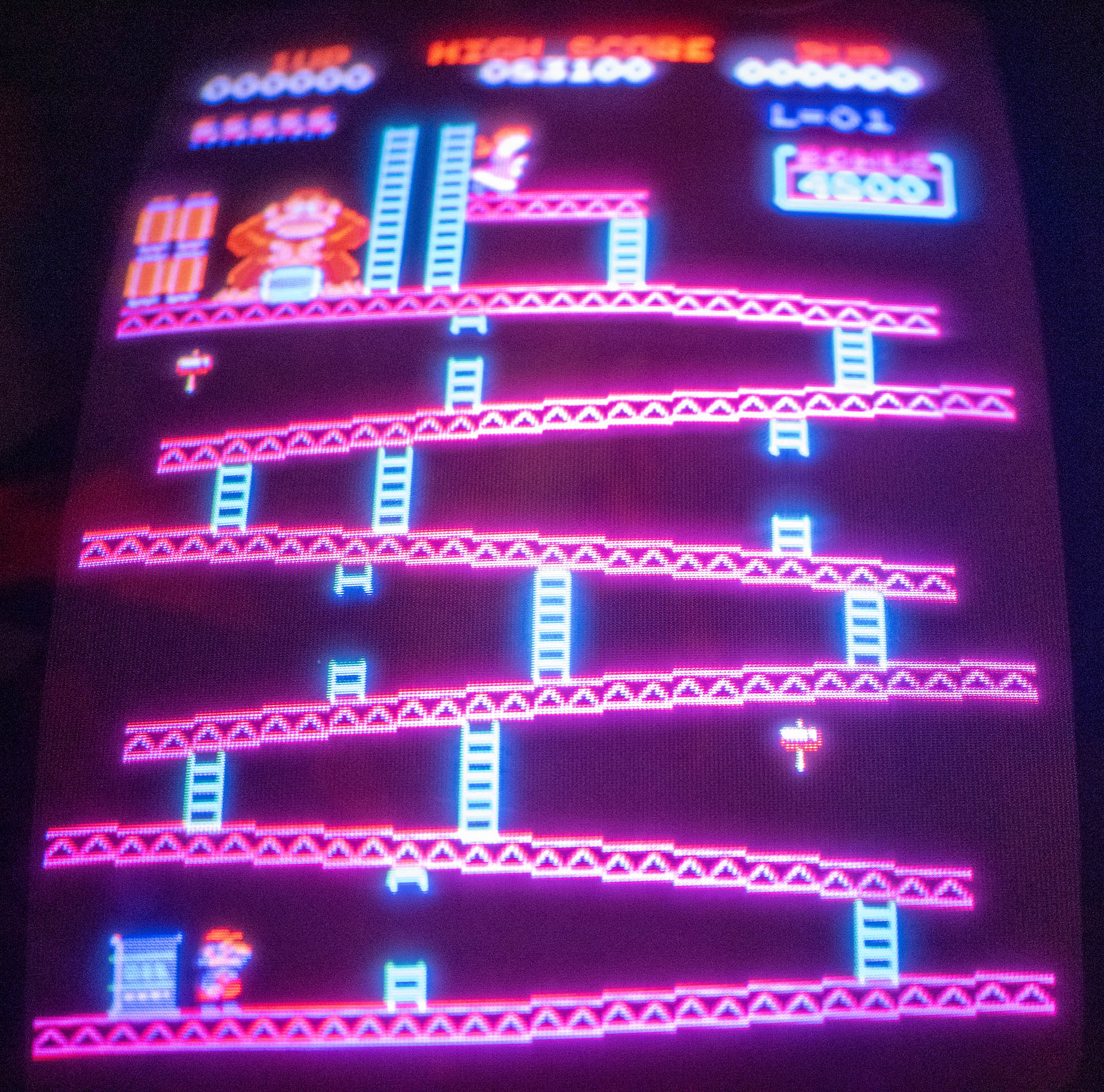

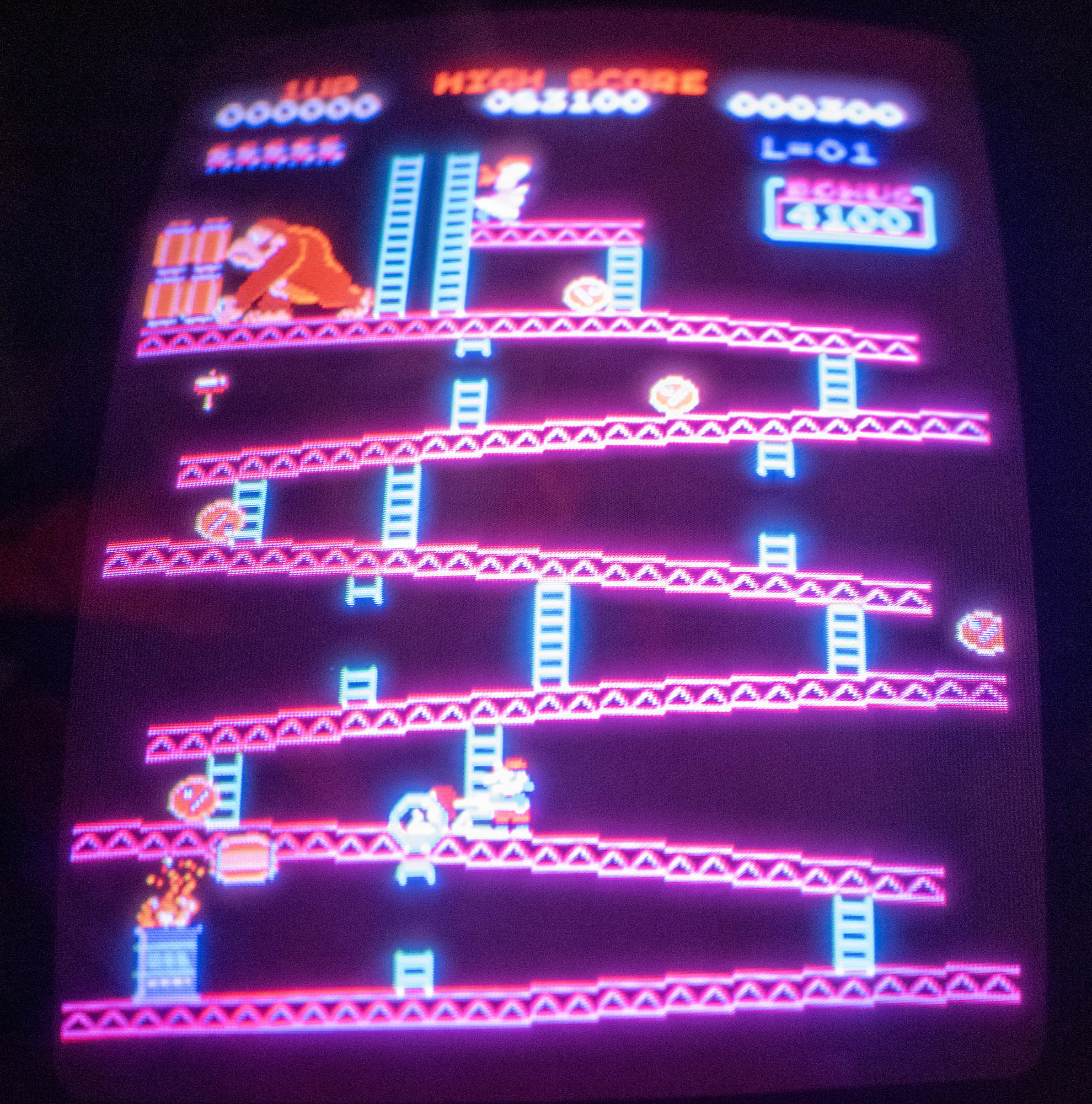

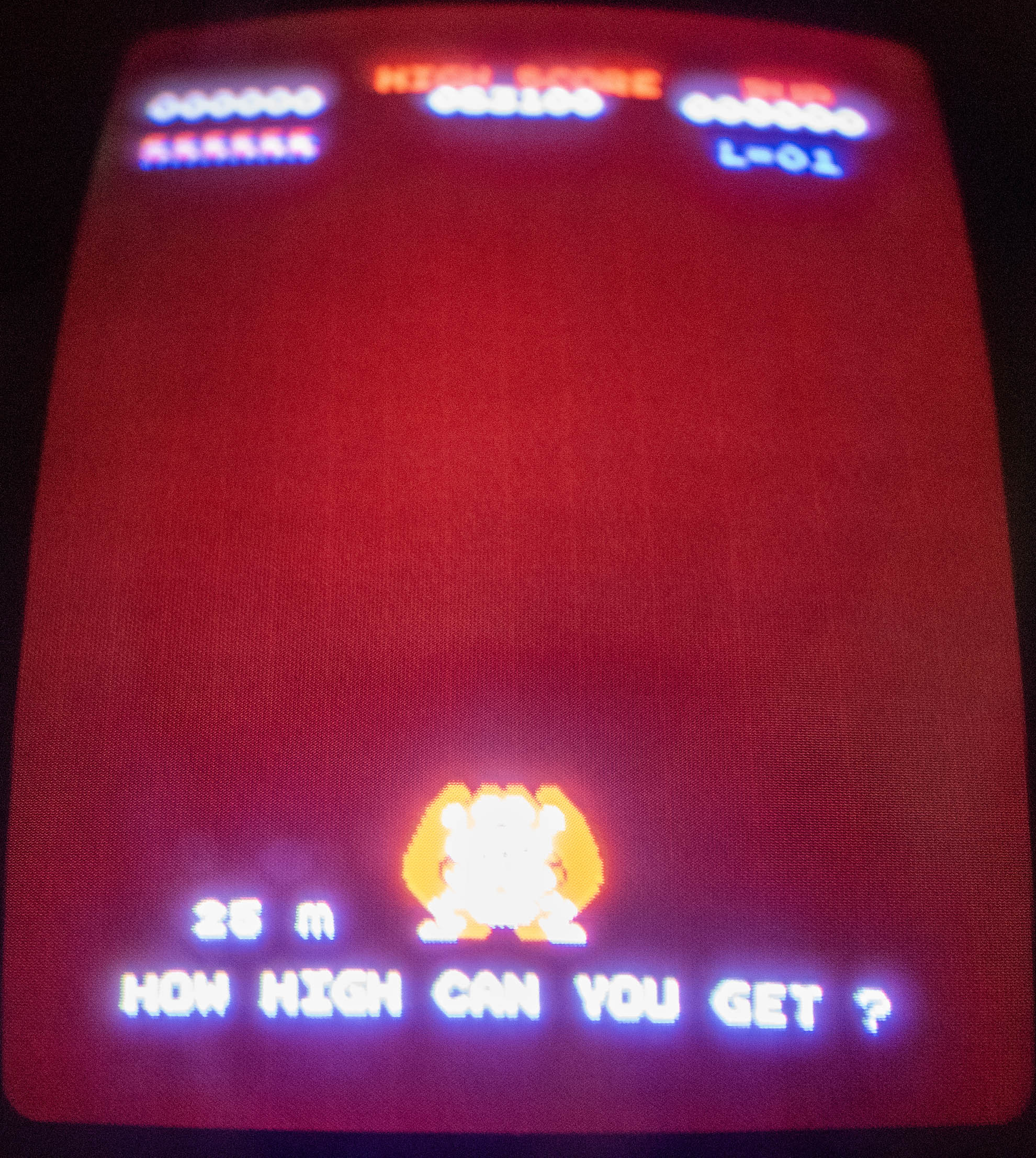

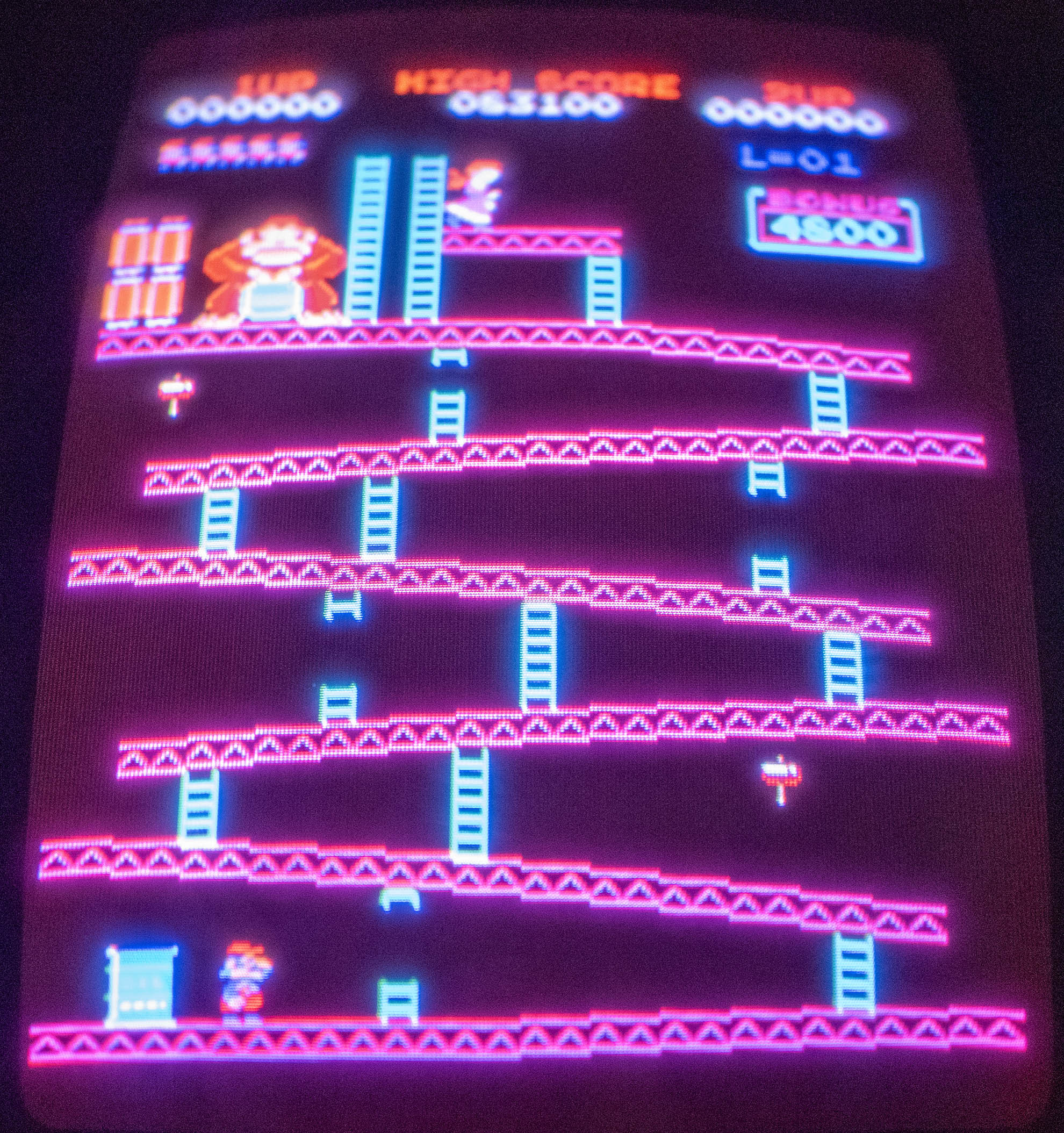

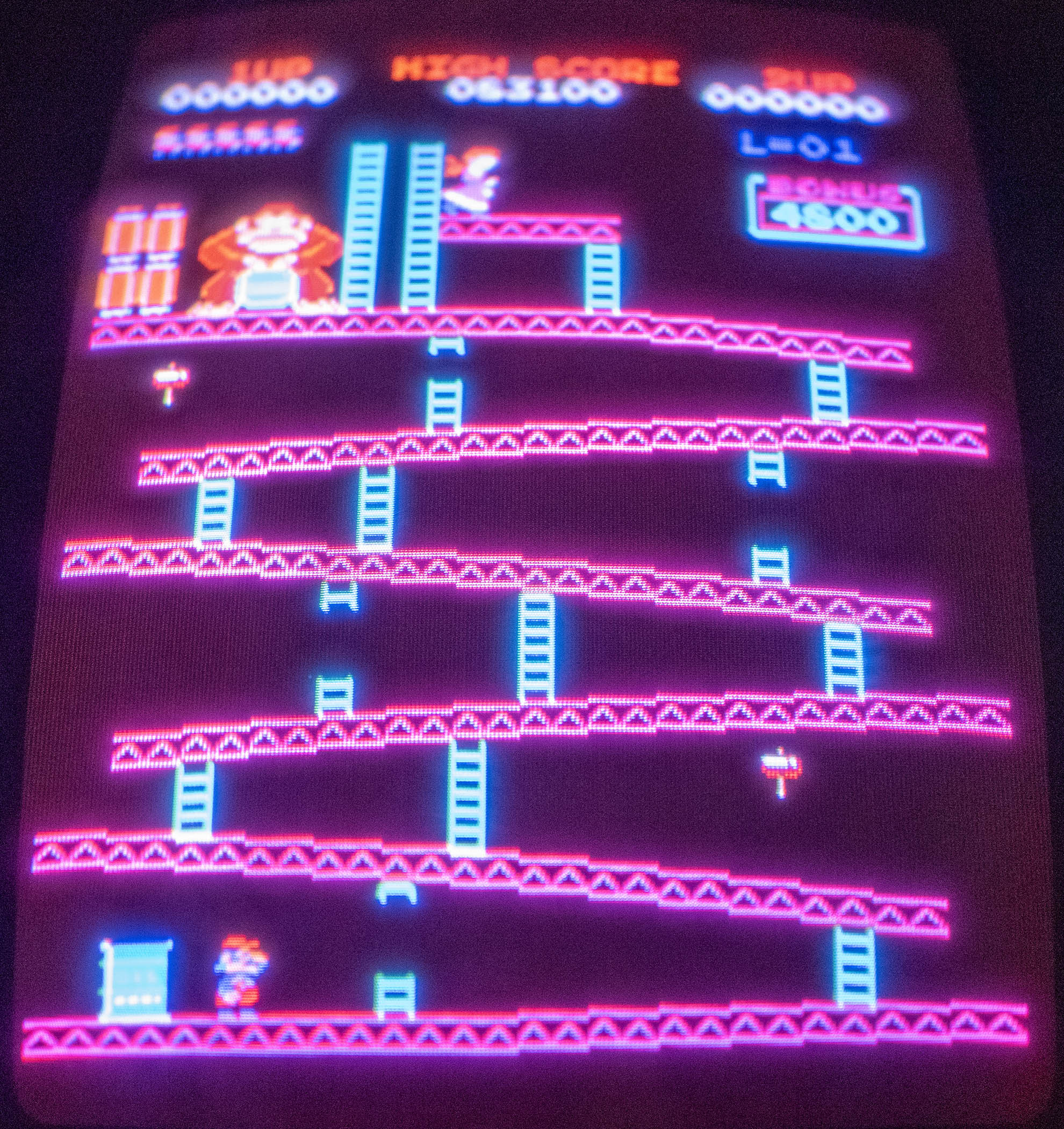

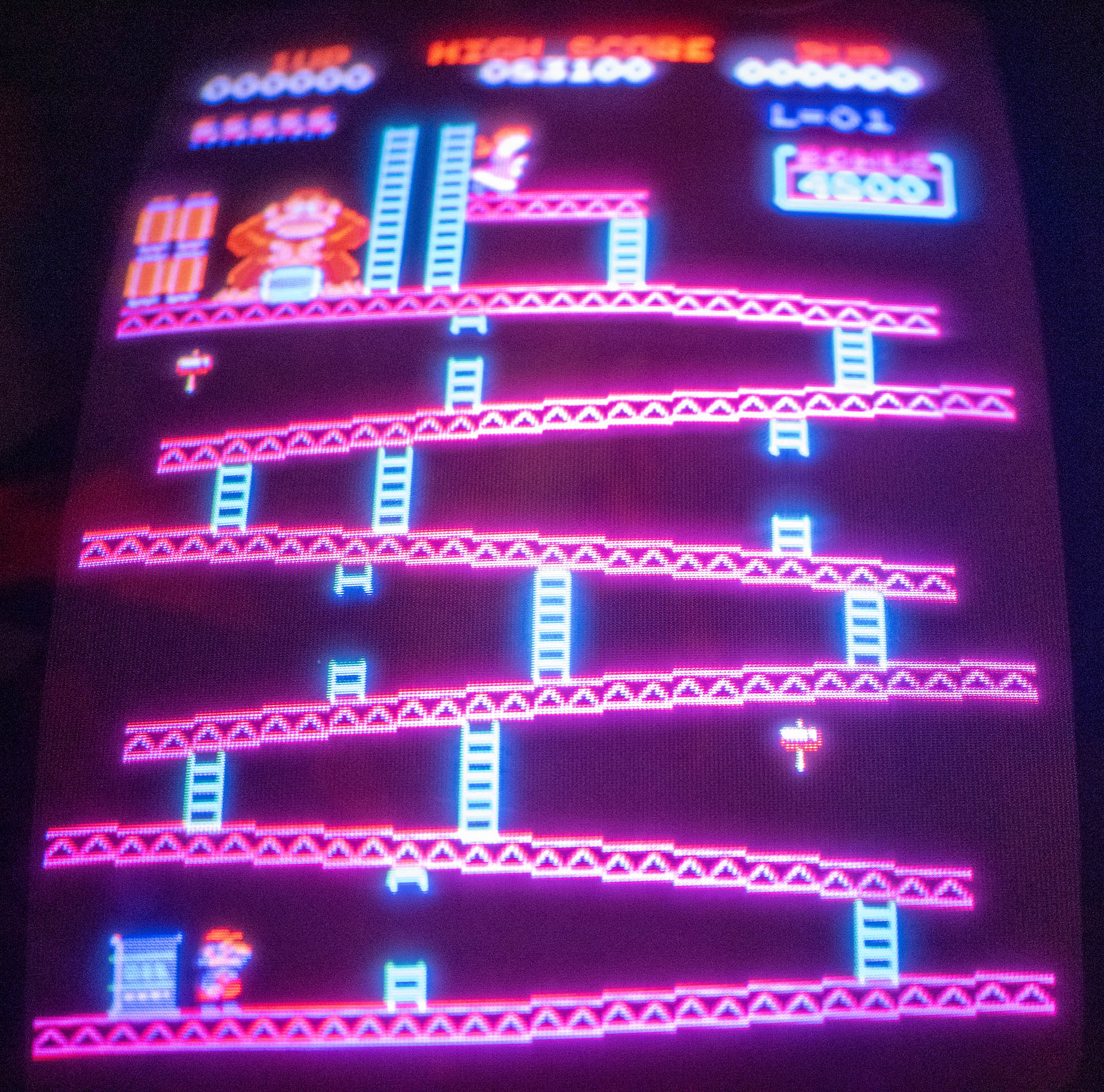

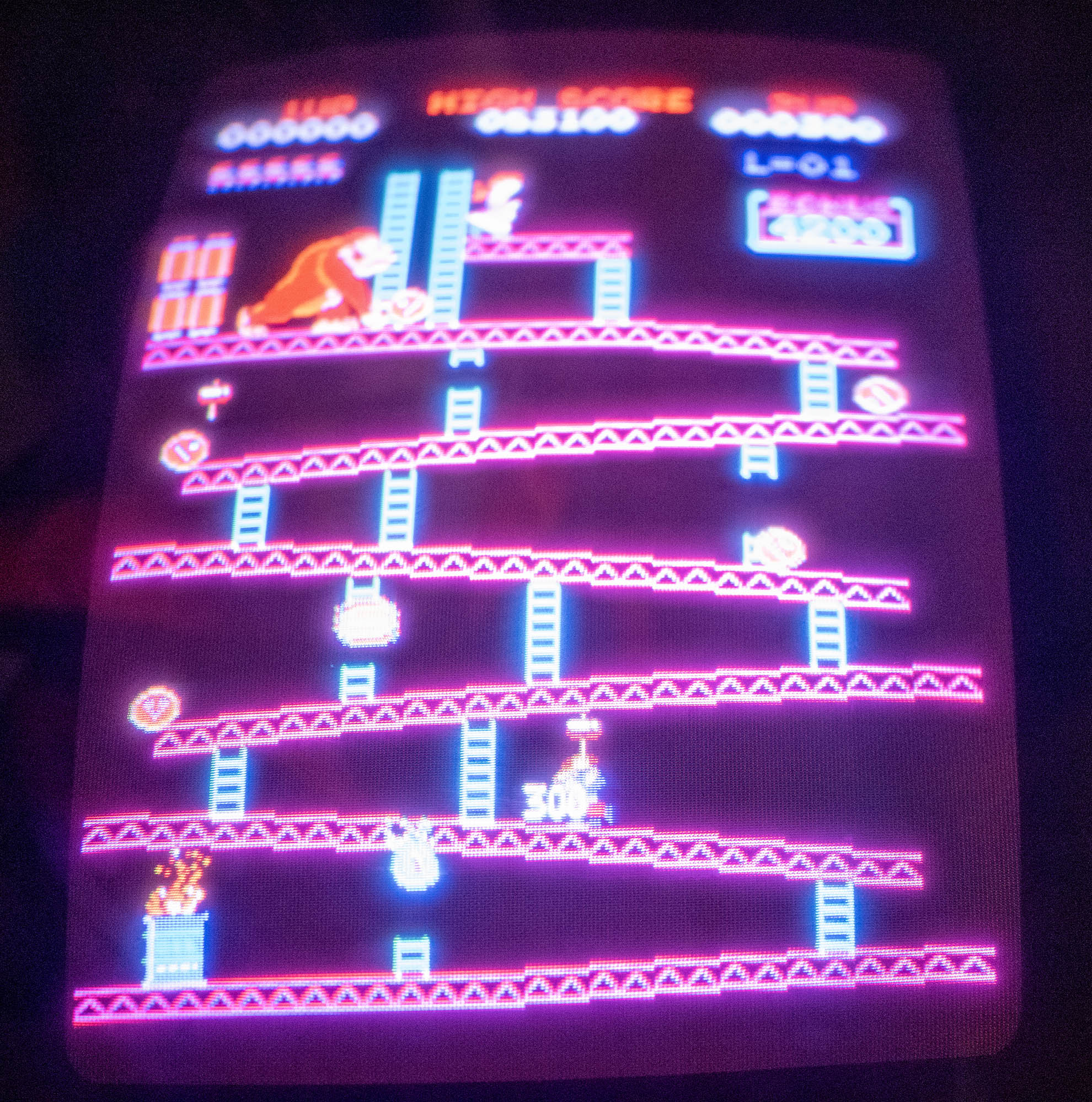

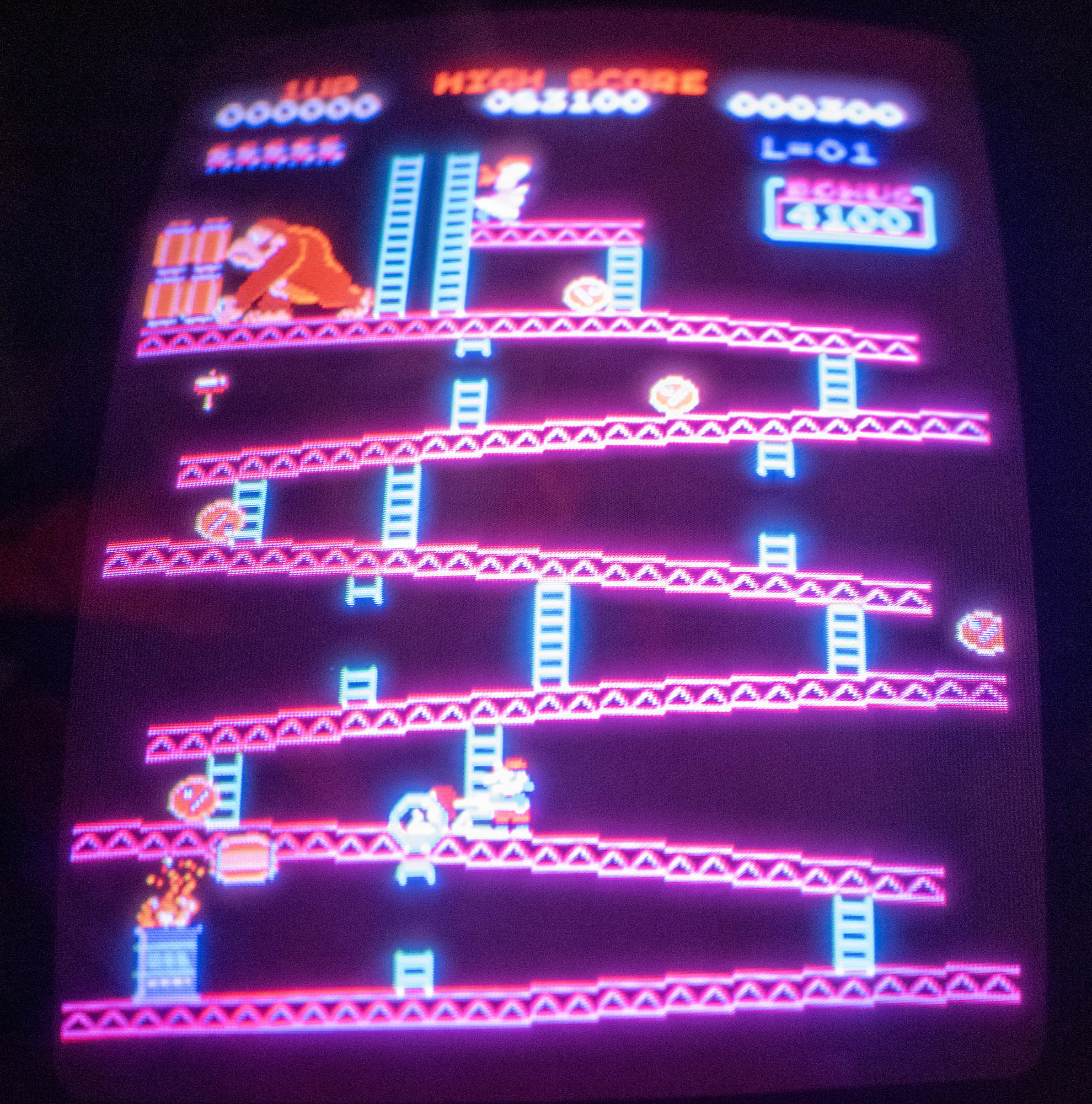

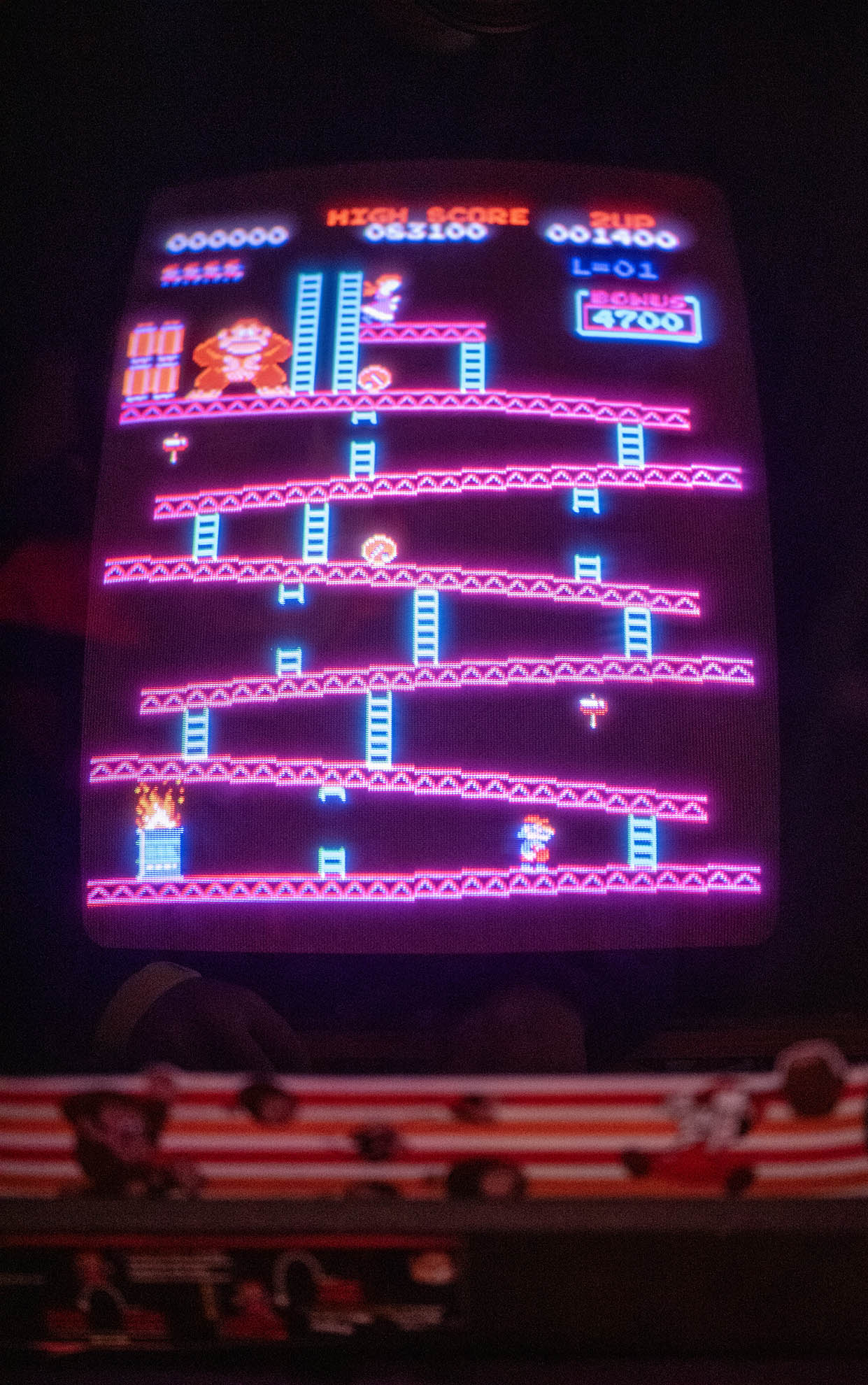

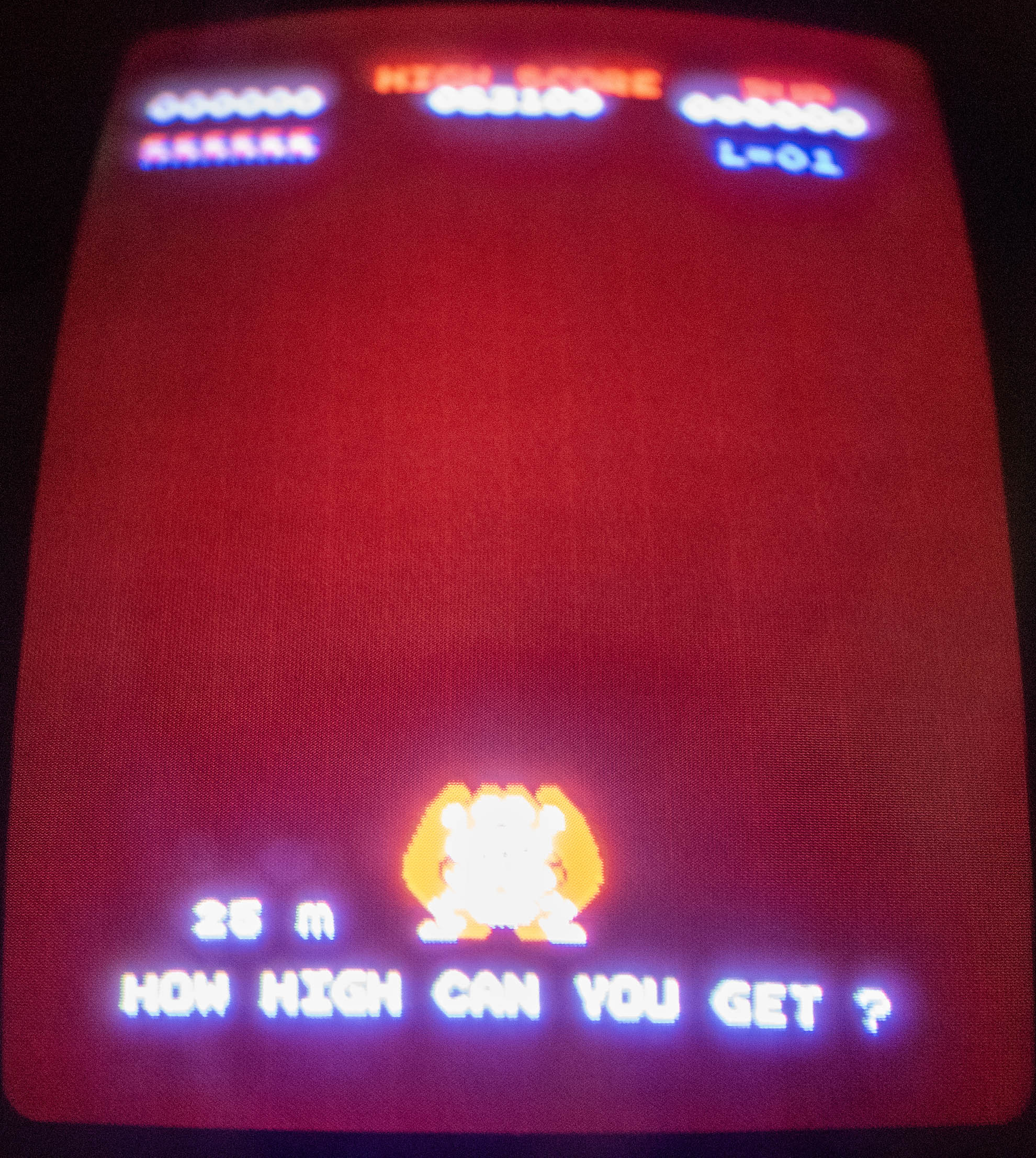

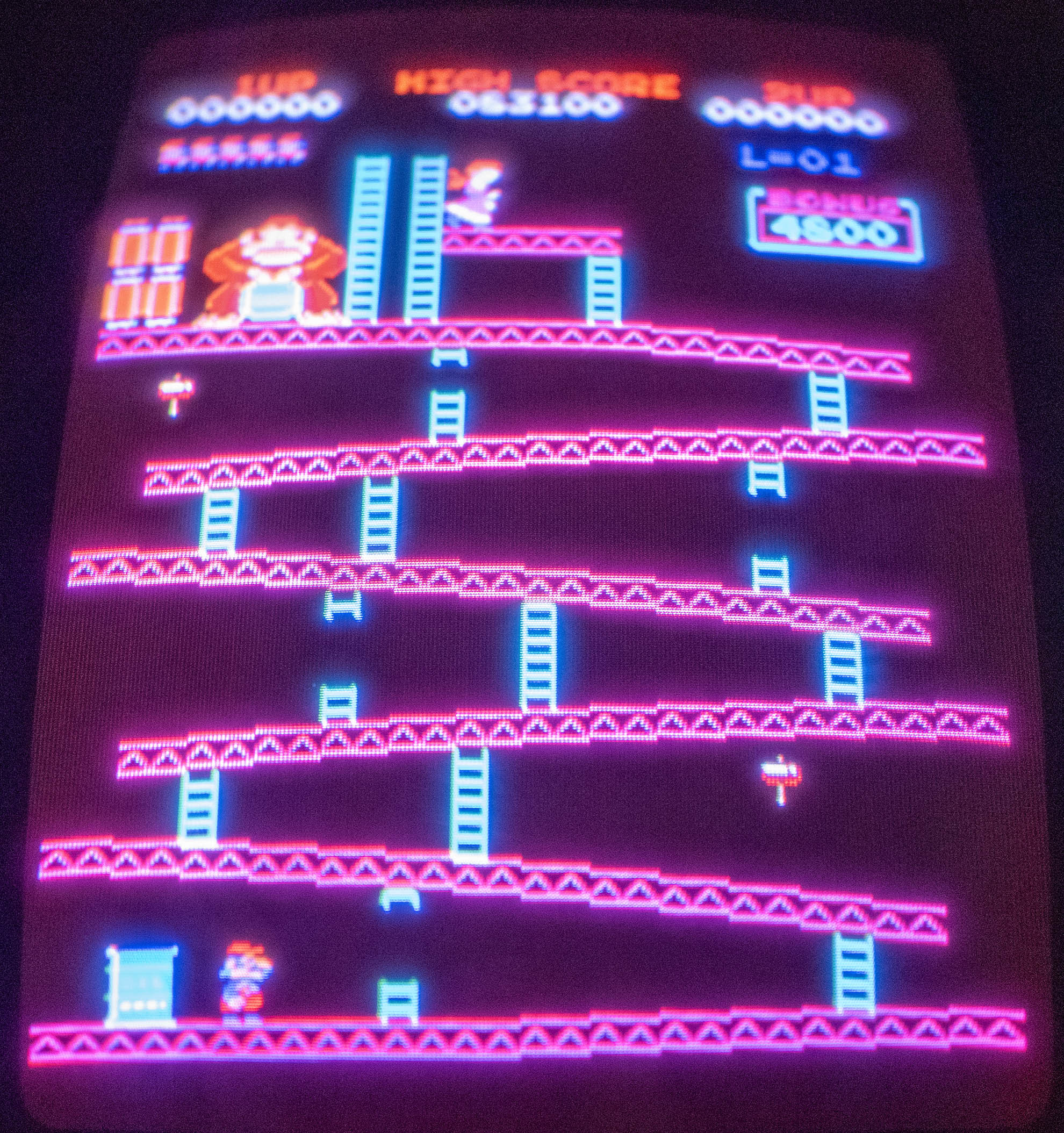

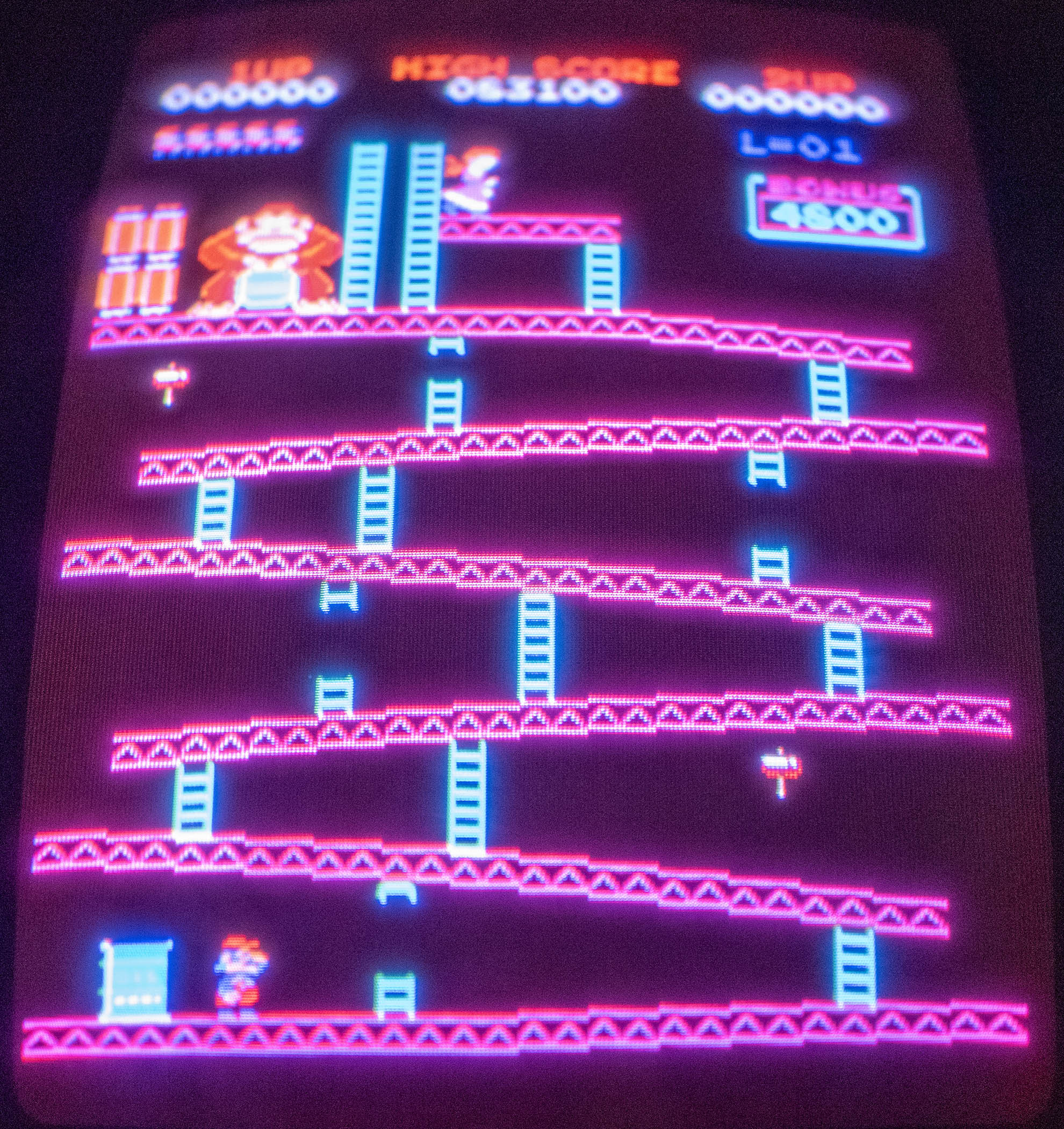

The final game featured four distinct stages, each set at a different height of a construction site. The cabinet's artwork actually displayed these heights: 25 meters, 50 meters, 75 meters, and 100 meters.

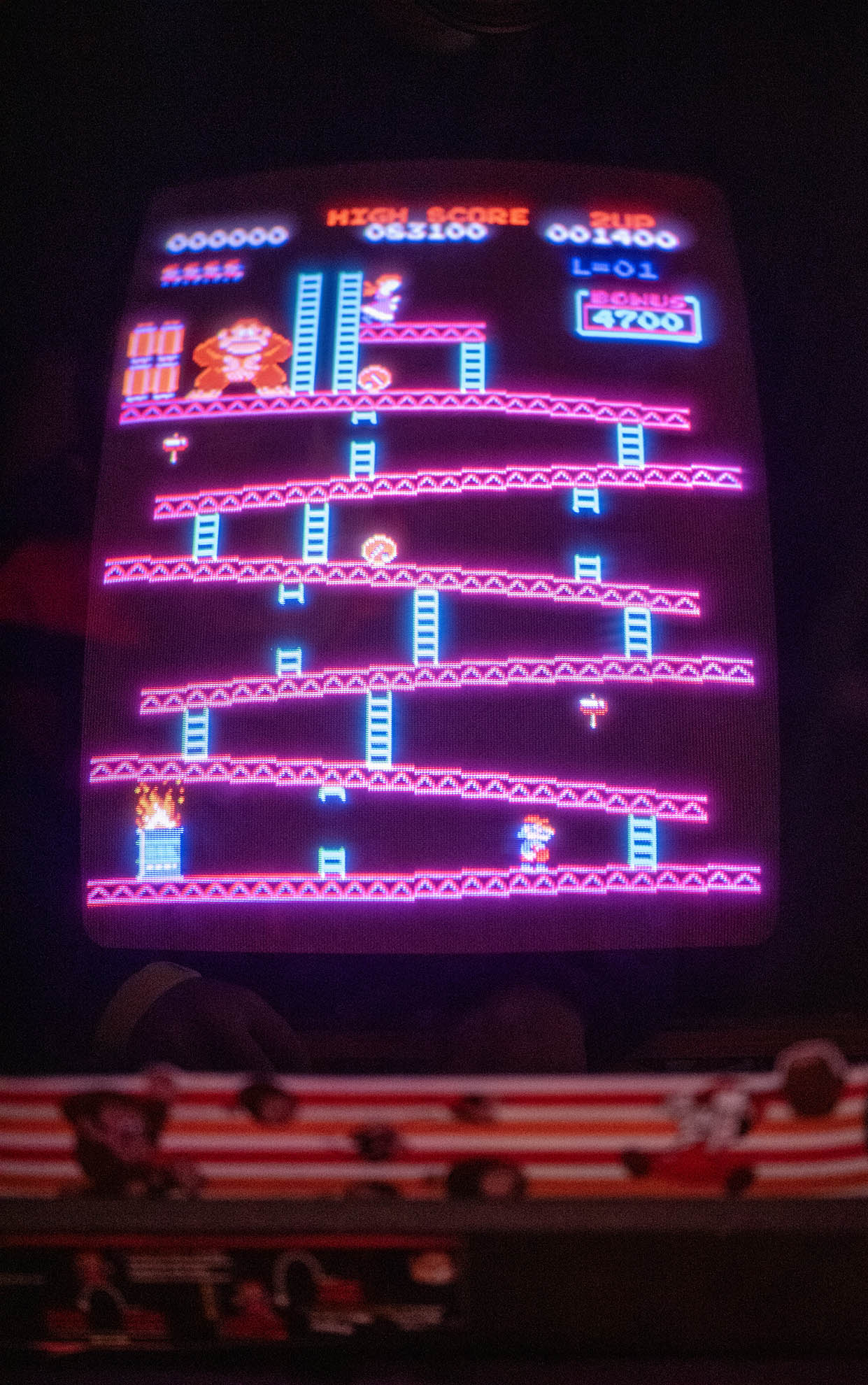

Stage 1 (25m) is the one everyone remembers. The player climbs crooked girders while Donkey Kong hurls barrels from the top. An oil drum at the bottom catches some barrels and ignites them into bouncing fireballs. A hammer power-up lets you smash through obstacles, but only for a few precious seconds.

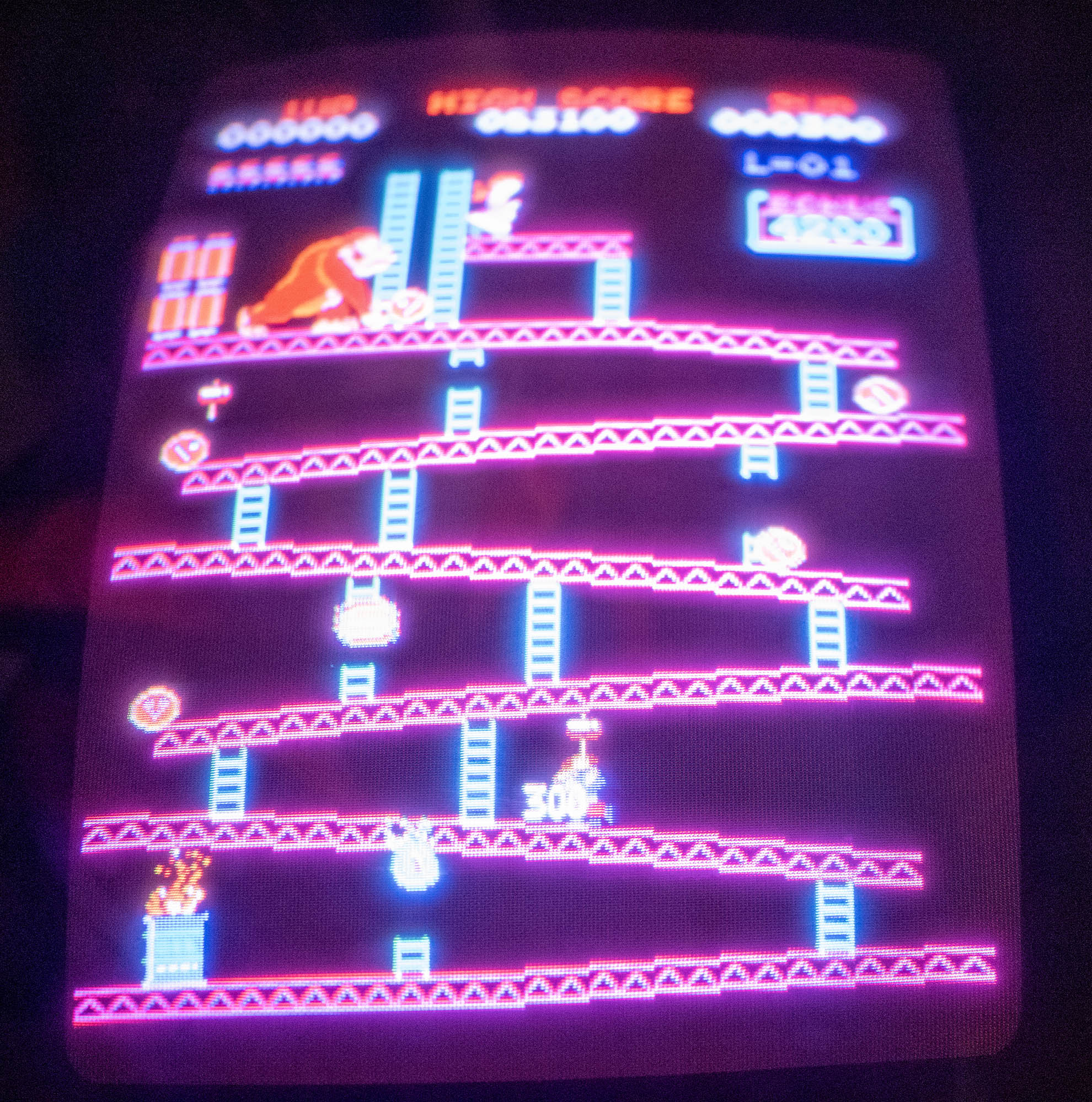

Stage 2 (50m) introduced conveyor belts carrying what looked like cement pans, though players often called them pies. This stage became infamous for a different reason. It was cut from almost every home port of the game due to memory limitations. If you only played Donkey Kong on the NES or ColecoVision, you might not even know this stage exists.

Stage 3 (75m) featured elevators and bouncing spring-weights. Getting crushed by the ceiling or clipped by a spring became a rite of passage for arcade kids.

Stage 4 (100m) changed the objective entirely. Instead of reaching Pauline, you had to remove eight rivets from the structure, causing it to collapse and sending Donkey Kong tumbling to his defeat. It was a clever reversal that made the final stage feel genuinely climactic.

After completing all four stages, the game looped with increased difficulty. It would continue looping until you ran out of lives or, if you were extraordinarily skilled, reached the kill screen at level 22.

The Kill Screen

Donkey Kong wasn't designed to have an ending. The developers assumed nobody would ever play long enough to see the game break. They were wrong.

Due to a bug in how the bonus timer calculates, stage 22 gives players only a few seconds to complete each screen. It's effectively impossible. The timer underflows, the game becomes unbeatable, and that's where your run ends.

This "kill screen" would later become central to one of gaming's most dramatic rivalries, but that's a story for later.

The Birth of a Hero

The squat carpenter in the red cap remained nameless in the Japanese release. When Nintendo of America received the game, they needed to write an instruction manual. Someone, the story varies depending on who tells it, decided to call him "Jumpman."

But that name didn't stick. According to the most popular account, Nintendo of America was renting their Tukwila warehouse from a man named Mario Segale. One day, Segale showed up demanding overdue rent. A heated argument ensued, with Nintendo's small team eventually convincing their landlord that payment was coming.

After Segale left, someone joked that they should name the character after him. The name stuck.

There's an alternate version from Don James, the warehouse manager, who claims they named the character Mario as a joke because Segale was so reclusive that none of the employees had ever actually met him. Either way, the result was the same.

Mario Segale himself seemed bemused by his accidental fame. In a 1993 interview with The Seattle Times, he quipped, "You might say I'm still waiting for my royalty checks."

He passed away in 2018, having never received those checks but having achieved a kind of immortality most landlords can only dream of.

$280 Million in Quarters

Remember those 2,000 Radar Scope cabinets sitting in the warehouse? A skeleton crew of just six people, including Arakawa and his wife Yoko, converted every single one of them into Donkey Kong machines. They worked around the clock, swapping out circuit boards and applying new artwork.

The gamble paid off beyond anyone's wildest expectations.

By October 1981, just three months after the Japanese launch, Donkey Kong was selling 4,000 units per month. By June 1982, Nintendo had sold 60,000 cabinets in the United States alone, earning $180 million in revenue. The following year added another $100 million. The game became the highest-grossing arcade title of 1981 in Japan and the highest-grossing of 1982 in America.

In total, Nintendo sold approximately 132,000 Donkey Kong arcade units worldwide: 65,000 in Japan and 67,000 in the United States. The total revenue reached $280 million by the end of 1982, equivalent to nearly a billion dollars today.

Nintendo of America wasn't just saved. It was transformed from a struggling importer into a genuine powerhouse.

Universal's Expensive Mistake

Success attracted attention, and not all of it was welcome. In June 1982, Universal Studios came knocking. Sid Sheinberg, president of MCA and Universal, believed that Donkey Kong infringed on Universal's King Kong trademark. He wanted royalties. Lots of them.

Universal's lawyers went after Nintendo's licensees first. Coleco, which had secured the rights to make home versions of Donkey Kong, initially caved and agreed to pay a 3% royalty. It seemed like Nintendo might have to do the same.

But Nintendo's lawyer, Howard Lincoln, smelled something fishy. He hired an attorney named John Kirby to dig deeper.

What Kirby discovered was remarkable. Just seven years earlier, in 1975, Universal had sued RKO Pictures over King Kong. Universal's own lawyers had successfully argued that King Kong was in the public domain, meaning nobody owned exclusive rights to the character or name. Universal had won that case. Now they were trying to claim the opposite.

Judge Robert Sweet didn't take kindly to this contradiction. He ruled that Universal had acted in bad faith, that they had no exclusive rights to King Kong, and that no reasonable consumer would confuse a "comical" video game ape with the cinematic monster. He noted that the two properties "have nothing in common but a gorilla, a captive woman, a male rescuer, and a building scenario."

Universal didn't just lose. They had to pay Nintendo $1.8 million in damages and legal fees. As a thank-you, Nintendo gave John Kirby a $30,000 sailboat named "Donkey Kong" and allegedly named their puffy pink video game character after him years later.

Bringing the Kong Home

The home console market wanted a piece of Donkey Kong too. Coleco secured the rights and released versions for the ColecoVision, Atari 2600, and various other platforms.

The ColecoVision version, bundled with the console itself, was a masterstroke. Over 2 million ColecoVisions shipped with Donkey Kong included, helping establish the system as a serious competitor. Coleco eventually sold 6 million Donkey Kong cartridges across all platforms, grossing $153 million and earning Nintendo over $5 million in royalties.

The Atari 2600 version, ported by Garry Kitchen under brutal deadline pressure (he reportedly worked 72 hours straight before shipping), sold 4 million units for $100 million. It became the third best-selling Atari cartridge ever, behind only Pac-Man and Space Invaders.

Nintendo's own Game & Watch version deserves special mention. Released on June 3, 1982, with model number DK-52, it featured two screens in a clamshell design. This version sold an astounding 8 million units. More importantly, it introduced the cross-shaped directional pad that would become standard on virtually every game controller made since.

The NES/Famicom port arrived in 1983. Due to memory constraints, it famously omitted the 50m "Pie Factory" stage. Most players never missed what they didn't know existed.

The King of Kong

Donkey Kong's competitive scene exploded decades after its release, thanks largely to a 2007 documentary called "The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters." The film followed Steve Wiebe, a schoolteacher, as he attempted to break Billy Mitchell's long-standing high score record.

Wiebe became the first person to score over one million points, achieving 1,006,600 on July 4, 2004. The documentary portrayed Mitchell as a villain and Wiebe as an underdog, though reality was considerably more complex.

The story took a dramatic turn in 2018 when Twin Galaxies, the organization that tracks arcade high scores, determined that Mitchell had used emulation software rather than original hardware to achieve his records. This was a violation of the rules. Mitchell was stripped of his scores and banned from submitting future ones. Wiebe was officially recognized as the first million-point scorer.

Today, the record stands at an almost incomprehensible 1,276,700 points, set by Robbie Lakeman in 2023. Competitive Donkey Kong remains active, with players constantly developing new strategies to squeeze out a few more points before hitting that level 22 kill screen.

The Legacy That Built an Empire

Donkey Kong's influence extends far beyond its own success. The game's hardware became the foundation for the Nintendo Entertainment System. When Nintendo approached semiconductor manufacturer Ricoh about designing chips for a home console, they brought a Donkey Kong arcade cabinet for analysis. The NES's Picture Processing Unit was directly evolved from that arcade hardware.

And then there's Mario. That squat little carpenter, renamed from Jumpman and given a plumbing career, went on to star in games that have collectively sold over 800 million copies. He's the best-selling video game character of all time, far outpacing franchises like Pokemon, Call of Duty, and Grand Theft Auto.

Guinness World Records officially recognizes Donkey Kong as the first platform video game. It was also the first game to use cutscenes to tell a complete story, with animated sequences showing Donkey Kong climbing the construction site with Pauline and the reunion at the end of each loop.

Technical Specifications

For the hardware enthusiasts, Donkey Kong ran on a Zilog Z80 processor clocked at 3.072 MHz, with an Intel 8035 handling sound at 400 KHz. The game displayed at approximately 224 by 256 pixels. Players used a four-way joystick and a single button for jumping.

The original cabinets came in two main varieties. Red cabinets (designated TKG2 and TKG3) were either converted Radar Scope machines or early purpose-built units. The classic blue cabinets (TKG4) came later and are what most people picture when they think of Donkey Kong. Ironically, the rarer red cabinets are now more valuable to collectors.

A Game Made by Outsiders

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Donkey Kong is who created it. Shigeru Miyamoto, the designer, had never made a game before. The Ikegami programmers had never made a game before. Even Gunpei Yokoi, the supervisor, was primarily known for hardware and toys rather than arcade software.

They brought no preconceptions about what a video game should be. They just made something fun. Miyamoto wrote the story before the gameplay was finalized, something almost unheard of in 1981. He created characters with personality in an era of abstract sprites. He built a world with internal logic and a clear narrative arc.

That freedom, born from inexperience, resulted in something genuinely new. Donkey Kong didn't just save Nintendo of America from bankruptcy. It established templates that the entire industry would follow for decades.

The next time you see Mario, whether he's racing go-karts, playing tennis, or saving yet another princess, remember where he came from. A dusty warehouse in Washington. A failed Popeye license. A landlord demanding rent. And a young artist who had never designed a video game, given the chance to create something that would change everything.

All arcade cabinet photos taken by the author at The Pixel Bunker.

For more arcade history, see Street Fighter II and Gyruss.\n\n## A Warehouse Full of Problems

Game Information

| Title | Donkey Kong |

| JP Title | ドンキーコング |

| Developer | Nintendo R&D1 / Ikegami Tsushinki |

| Designer | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Supervisor | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Composer | Yukio Kaneoka |

| Release | July 9, 1981 (Japan) |

| Platform | Arcade (Z80-based) |

| Genre | Platform |

| Players | 1-2 (alternating) |

| Arcade Units | 132,000+ |

| Revenue | $280 million (1981-82) |

Gallery

Get Gaming News and Features First

Stay updated with the latest gaming news and exclusive content.